🔸Introdución á harmonía, cadencias e finais de frase

John Peterson

PUNTOS PRINCIPAIS

Este capítulo serve de introdución á harmonía neste libro, e despois trata a creación dunha sensación de conclusión da frase. Centrámonos exclusivamente nos acordes do I e o V de momento.

Hai dous conceptos importantes que inflúen na maneira en que presentamos a harmonía: a función harmónica e o modelo de frase.

Os finais están marcados moitas veces por cadencias, das cales hai dous tipos principais: cadencias auténticas e semicadencias.

A cadencia auténtica contén a progresión V-I. É perfecta cando os dous acordes están estado fundamental e a tónica (1ˆ) está na voz da soprano sobre o I. Se non se cumpre calquera destas dúas condicións, a cadencia auténtica é imperfecta.

A semicadencia (ou media cadencia) contén a progresión x-V, onde x é un de varios acordes posibles.

LISTA DE REPRODUCIÓN DO CAPÍTULO

Introdución á harmonía

Nesta sección, centrarémonos en ver como se usa a harmonía nas frases da música dos estilos da "práctica común" da música occidental (barroco, clasicismo e romanticismo). A harmonía é un compoñente importante, entre outros, para crear na frase a sensación de movemento cara a un obxectivo. Ao estudarmos a harmonía, é importante ter claros dous conceptos relacionados: a función harmónica e o modelo da frase.

A función harmónica distingue tres tipos de acordes:

Tónica (T): Os acrodes que soaen estables e dan a sensación de centro ou inicio. Na música clásica occidental, o único acorde que cumpre estas características é o I (nomodo menor: i)

Pre-dominante (PD) ou subdominante: Os acordes que fan unha transición entre a función da tónica e a da dominante. Esta categoría pode dividirse en dous grupos:

Pre-dominantes fortes, que indican que a dominante é inminente: IV ou ii (no modo menor: iv e iiº)

Pre-dominantes débiles, que se apartan da tónica e normalmente van a unha pre-dominante máis forte: iii ou vi (no modo menor: III e VI e tamén a subtónica, VII)

Dominante (D): Os acordes que dan unha sensación de necesidade de resolver na tónica: V ou viiº (no modo menor son iguais).

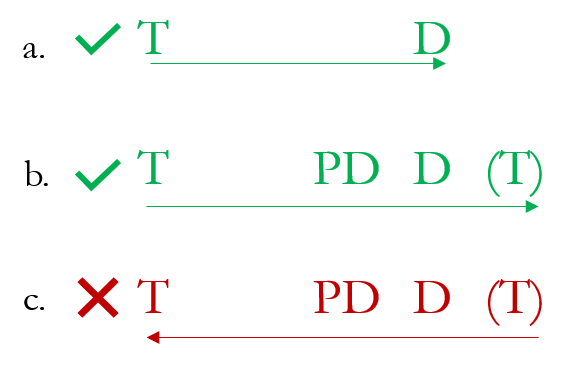

O modelo da frase é a orde típica do fluxo de funcións harmónicas dentro dunha frase. O esencial do modelo da frase é que ten que haber polo menos unha harmonía con función de tónica e outra con función de dominante para dar sensación de traxectoria. É habitual que as frases inclúan tamén unha harmonía con función pre-dominante para enfatizar esa sensación de traxectoria cara á conclusión. As frases case sempre progresan de esquerad a dereita neste modelo de frase, aínda que veremos algunhas excepcións máis adiante. Podes ver un resumo no Exemplo 1.

Introdución ás cadencias

Unha forma de crear sensación de conclusión no final dunha frase é mediante unha cadencia: un padrón melódico e harmónico que crea obxectivos concretos, como os signos de puntuación nas frases literarias. Son importantes porque poden servir para determinar cando acaba cada frase, mais tamén porque nos axudan a ver a tonalidade dun fragmento. Por este motivo, escoitar as cadencias é unha bo primeiro paso nunha análise.

O Exemplo 2 mostra dúas frases os dous tipos principais de cadencia: (1) suspensiva e (2) conclusiva. A primeira frase finaliza no c. 4 cunha semicadencia (SC), que soa suspensiva. A segunda frase comeza no c. 5 e remata no c. 8 cunha Cadencia auténtica, que soa conclusiva. As siglas CAP indican que se trata dun tipo concreto de cadencia auténtica, que se chama Cadencia Auténtica Perfecta, como veremos máis adiante.

Exemplo 2. Dúas cadencias nesta obra de Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges: o “Ballet No. 6” de L’amant anonyme, Acto II (0:00–0:07).

Cadencias Auténticas (soan conclusivas!)

An authentic cadence occurs when the harmonic progression V–I (or V–i in minor) marks the end of a phrase. There are two kinds of authentic cadence:

A perfect authentic cadence (PAC) occurs when both of the following conditions are met (Example 2, m. 8):

Do is in the soprano over the tonic chord

Both V and I are in root position

An imperfect authentic cadence (IAC) occurs if either of the above two conditions isn’t met, but V–I is still involved (Example 3). For instance, an IAC can occur when:

Mi (me in minor) is in the soprano over the tonic chord (as in Example 3), or

V, I, or both harmonies are inverted

Example 3. An imperfect authentic cadence (IAC) in Fanny Hensel, “Ferne” Op. 9, No. 2 (0:00–0:14).

Half Cadences (they sound inconclusive!)

A half cadence (HC) occurs when a phrase ends on V (Example 2, m. 4). A variety of chords can precede V, so we often refer to the harmonic progression that marks HCs as “x–V.”

For now, we’ll restrict our vocabulary to only I and V chords (or i and V in minor) so we can learn some basic techniques of voice-leading.

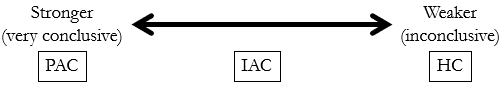

Cadential Strength and the IAC

PACs are the strongest kind of cadence available to a composer because of the sense of finality they can create, and HCs are the weakest kind of cadence because of their unfinished sound. IACs are special because they occupy the space between HCs and PACs in terms of cadential strength (Example 4).

Since there are many ways to compose an IAC (a composer can theoretically use various combinations of inverted chords and scale degrees in the melody), a composer can choose to make an IAC more or less strong.

The cadence in Example 3 above is relatively strong: it uses root position V–i with me in the soprano, it comes at the end of a sentence in the lyrics, it uses a half note, it’s followed by a rest, and the music that follows sounds like a new phrase.

The potential IAC in Example 5 is comparably weaker: it uses V6–I, the moment goes by relatively quickly, and it’s followed by material that could easily be understood as continuing a phrase that’s under way or as referencing the beginning of a phrase that has just concluded, something that would strengthen reading m. 5 as an IAC. Performers may disagree on whether Example 5 contains an IAC or not, and they may adjust their playing accordingly.

Example 5. A potential IAC in Schubert’s Piano Sonata D. 845, III.

An additional complication is that composers often avoid creating a PAC using progressions that fit the description of an IAC, but that don’t mark the end of a phrase. In Example 6, m. 8 contains a potential IAC, but when m. 9 begins to repeat the material from m. 5 (compare the bass voice in m. 9 with the soprano in m. 5) it sounds like the passage is trying the run-up to the cadence again to achieve something stronger than the potential IAC at m. 8. We indicate that the cadence in m. 8 is subverted by crossing the label out on the score.

Example 6. Avoiding a cadence in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 2, no. 3, I, mm. 1–13.

With so many possibilities, how can we determine what counts as a true IAC? The next section (“Hearing Cadences”) offers some help.

Hearing Cadences

While there is certainly a degree of intuition involved with hearing cadences, it’s also a skill that can be honed over time. We recommend listening for cadences following this process:

SUMMARY: STEPS FOR HEARING CADENCES

Mark potential cadence points

Analyze the harmonies involved

Listen for a sense of beginning after each potential cadence point

At first, listen and mark potential points of rest, goal, or closure.

It’s common for students to initially mark too many cadences. One rule of thumb is that unless an excerpt’s tempo is quite slow, it’s not common for phrases to be two measures long.

Next, check the harmonies involved in these potential cadence points:

x–V = potential HC

V–I = potential AC

If do is in the soprano over I and both harmonies are in root position, it’s a potential PAC.

If something else like mi or sol is in the soprano over I, it’s a potential IAC.

If V, I, or both harmonies are inverted, it’s a potential IAC.

If it doesn’t involve one of the above two progressions, then it’s not a potential cadence. (Note that this doesn’t mean it doesn’t represent some kind of ending. It just means it’s not a cadence.[1])

Finally, listen for what happens after each potential cadence point.

Since true cadences mark the end of a phrase, it’s very common for cadences to be followed by a sense of beginning. This “beginning” may be a repetition of the beginning of the phrase that just ended, or it may be new material that starts a new phrase. Hearing a sense of beginning following a cadence point is a great way to help verify that what you’ve marked as a potential cadence is indeed a true cadence point.

If, instead, you hear repetition of material from the middle of the previous phrase, your potential cadence may not be a true cadence. Instead, it likely represents a potential cadence point that has been subverted.

Writing Authentic Cadences (with triads only)

The steps for writing a PAC or IAC are summarized in the box below and illustrated in Examples 7–10.

WRITING A PAC OR IAC

Determine the key

Write the entire bass: sol–do

Write the entire soprano:

PAC: re–do or ti–do or

IAC: re–mi or sol–sol or

Fill in the inner voices by asking:

What notes do I already have in the bass and soprano?

What notes do I need to complete the chord?

What note will I double? (Remember, in root position chords, it’s common to double the bass.)

If you’re writing in minor, remember that you need to use the leading-tone, ti , in your V chord (making it a major triad, not minor) to give it momentum toward the tonic.

Example 7. Writing a PAC in a major key.

Example 8. Writing a PAC in a minor key.

Example 9. Writing an IAC in a major key.

Example 10. Writing an IAC in a minor key.

Writing Half Cadences (using I and V only)

The steps for writing a HC are summarized in the box below and illustrated in Examples 11 and 12.

WRITING A HC:

Determine the key

Write the entire bass: do–sol (note: for now, we’ll use only I and V chords, although we’ll see later that other chords more commonly precede V)

Write the entire soprano: do–ti or mi–re or (note: sol–sol [ ] is possible, but not common)

Fill in the inner voices by asking:

What notes do I already have?

What notes do I need to complete the chord?

What note will I double? (Remember, in root position chords, it’s common to double the bass.)

If you’re writing in minor, remember to use the leading-tone, ti , in your V chord, making it a major triad, not minor.

Example 11. Writing a HC in a major key.

Example 12. Writing a HC in a minor key.

Assignments

Media Attributions

Phrase_Model © John Peterson is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

Example_3_Cadence_Strength_Spectrum

Notas a rodapé

Sometimes, for example, the melody suggests an ending, but the harmony doesn't participate. Or, sometimes the harmony suggests an end, but the melody refuses to close. Cadences are special goal points because they represent places where both the melody and harmony agree on a phrase ending. ↵

(en construción) Orixinal: https://viva.pressbooks.pub/openmusictheory/part/diatonic-harmony/

Last updated